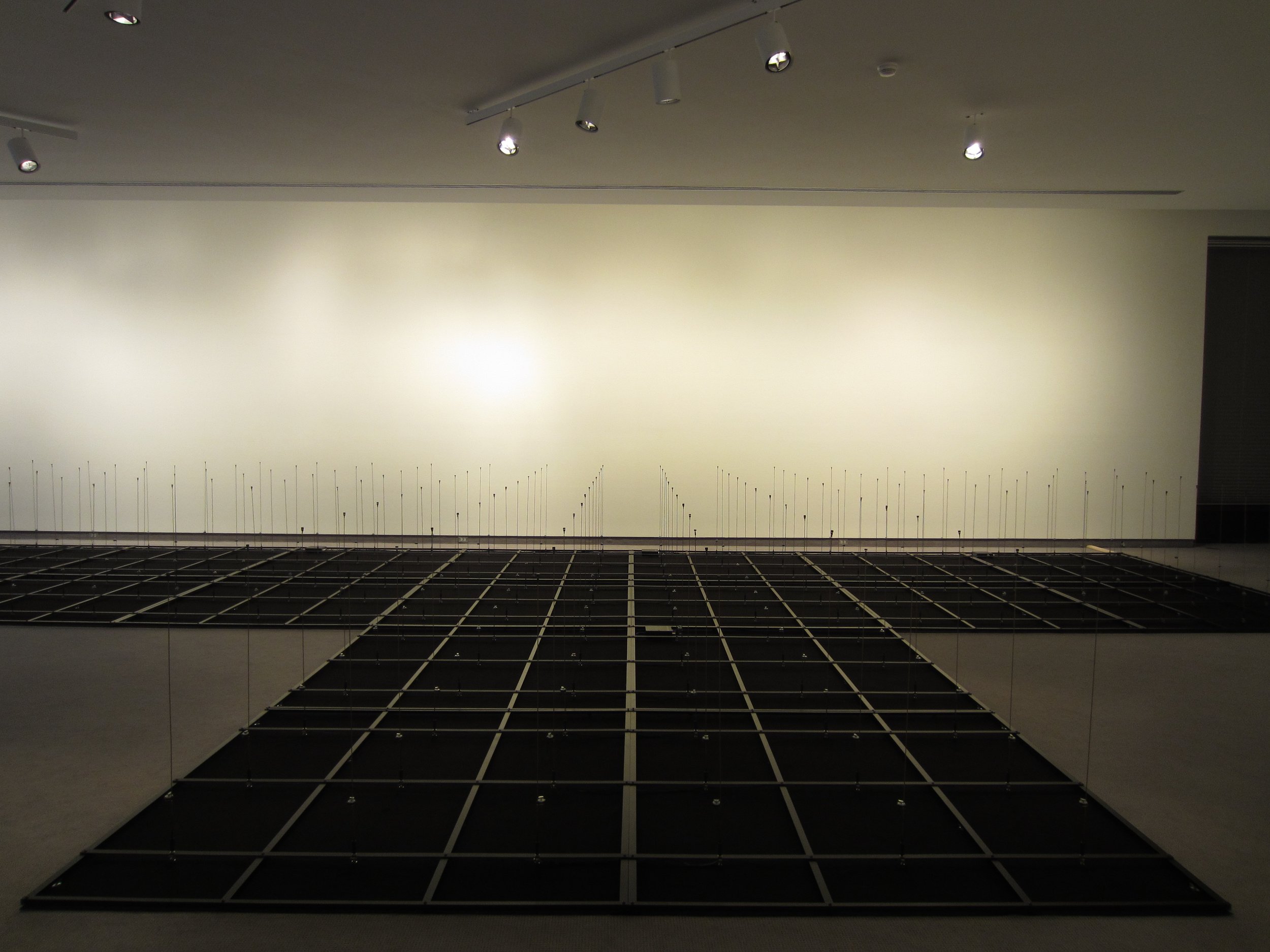

Prairie (2013)

Prairie is a large-scale electro-acoustic sound installation which was first installed at the Chicago Cultural Center from Feb 8 to May 5, 2013. This piece is made up of 432 thin rods with small speakers at the tip, and with vibration motors near the base. Each of these stems is independent, and issues small clicks and buzzes, controlled by a central computer program. Probably best is to quote from the curatorial text by curator Lanny Silverman - you will find this below - (the full gallery handout can be downloaded here as a pdf). But first, here is video and sound documentation of the piece. Scroll down to read the curator's statement.

Lanny Silverman:

Shawn Decker is a Chicago-based artist whose work blurs the boundaries among several media. Prairie functions ostensibly as sound sculpture, which subtly yet distinctly alters the ambience and acoustic experience of the gallery but also has a substantial presence as a work of physical sculpture. Sound sculpture has a rich history, at times grounded in a visual arts context, but also often derived from avant-garde musical composition. The Futurist experiment in extending our ideas of art and music in the early 20th century exemplifies this odd mixture. Luigi Russolo’s intonarumori were essentially machines that produced noises that were utilized in what was proposed as the new music of the machine age. Although they had a crude sculptural presence, their main contribution was in their extension of the idea of music to incorporate the sound and feel of the industrial era, as well as establishing a visual arts context for revolutionizing music. Jumping forward to the early 1960s, many kinetic artists also built on this foundation of machines as makers of music. Jean Tinguely was the master of this mode and his famous self-destroying sculpture titled Homage to New York (1960), at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City perhaps (ironically) realized 19th century composer Richard Wagner’s imaginings of a Gesamt- kunstwerk, or total work of art.

At this same time, in the music arena, John Cage extended our sense of “music” to include both noises from our environment and even so-called “silence” – as he would have us listen to all sounds impartially. He also brought chance operations into composition, further challenging notions of authorship. Into this fervid environment came Bill Fontana, a leader of what is now called sound sculpture. His early sound installations in the 1970s and 1980s tended to utilize acoustic urban environments as source material to be manipulated. Canadian artist Janet Cardiff is possibly the most prominent current practitioner of this art form, and her work has varied from urban audio tours blending documentary and fictional elements to reconfiguring Thomas Tallis’ early music into a sound installation.

Decker has been more directly influenced by the work of composer and theorist R. Murray Schaefer, who introduced the notion of “sound- scapes” in the 1970s, in which recorded natural sounds are liberated from their original source in order to create immersive acoustic environments. The generation of American avant-garde composers that followed Cage (such as Alvin Lucier, Annea Lockwood, David Behrman, and others) continued to explore natural phenomena and even bodily functions as part of musical composition and also the blurring of music and art contexts for presentation of work. Decker’s work is also a manifestation of recent developments in electronic music, particularly computer music, in which programming can create a subtle combination of composition and changing, unpredictable elements.

Prairie epitomizes Decker’s ongoing investigations into the complexities of rhythm, small motions, sounds and the dynamic behavior of natural systems. This piece mimics the rich soundscape and eco-systems of grasslands with insect sounds, rain, wind and other rhythms of the life found within them, while it also incorporates a visual recreation of tall grasses moving in the wind. The interplay between nature and the machine, human intervention and artifice is complex and multi-layered. The programming of this piece is an excellent example of this. Each of the multitudinous vertically mounted brass rods contains a vibration motor at the base and a small speaker at its top resulting in the “grass” stems shuddering and swaying as the speakers emit clicking and buzzing sounds, possibly suggesting a relationship between sound and motion. This is all controlled by a microprocessor with patterns generated by simple rules applied to each stem, so that they operate independently, but are also affected by neighboring stems’ actions as well. This interplay between structured patterns and chance is modeled after natural systems’ emergent behavior; thus Prairie’s ongoing changes mirror that of an eco-system responding to gradual changes in its natural environment. This interaction between programming and chance, between authorship (and intentionality) and “natural” can easily be seen as an evolution of John Cage’s compositional methods.

Rather than hide his process and the work’s structural underpinning, Decker has made this an important part of the work, and these design choices impact our experience of the work. Hence functional elements are also aesthetic choices. In addition to the irony of an artist “designing” a natural system – or at least a recreation of one, Decker has created a large-scale sculptural piece with nods to highly manufactured Minimalist sculpture of the 1960s as well as to the modernist grids evident in Modernist architecture, especially that of Mies van der Rohe. Again, the peculiar notion of “manufacturing” nature and the contrast between natural order and human order (which of course at some level is also natural) is complex and fascinating.

And lastly, the most important aspect of this piece is its performative, changing nature, meant to be experienced over a period of time. The artist has carefully constructed a work of art that evokes our experience of natural phenomena, an everchanging performance which isn’t entirely predictable. Over time, seeming “conversations” and patterns between the various stem elements have an almost hypnotic and sometimes even humorous appeal. Decker has created a work of art which subtly yet powerfully changes the ambience of this magnificent gallery surrounded by an ominously apt cityscape evident in window views. He has engineered an experience that slows down our internal sense of time, much like being in natural settings often does. Despite its seeming minimalism and subtlety it is also replete with musical, rhythmic, intellectual and aesthetic complexity that rewards the patience of its audience.